Minority Discounts are not always applicable to a Non-Controlling Interest

A minority discount refers to a reduction in the pro rata value of a non-controlling interest in a company. It reflects the premise that a partial ownership interest may be worth less than its proportional ownership in the entire business.

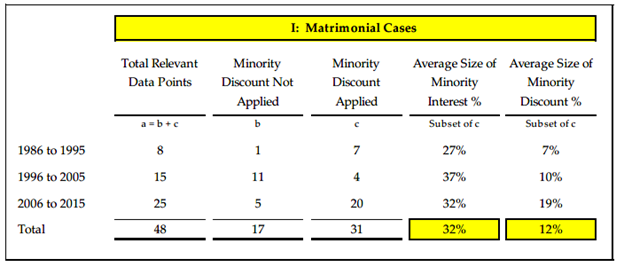

Minority discounts are typically applied when valuing businesses for various purposes, including family law cases. In a landmark 2017 research study1, the authors summarized the frequency and quantum of minority discounts applied by courts in matrimonial disputes. Their findings are summarized in the following table:

What is a Minority Discount?

A minority discount is meant to reflect the many disadvantages associated with not having control over the business, including decisions over:

- The future direction of the business such as the hiring or firing of employees, asset investments or liquidations, sale of the company, transfer of shares, etc.

- The amount of compensation paid to management and the amount and timing of dividend payments to shareholders.

What determines the size of a Minority Discount?

The size of a minority discount can vary based on a variety of factors, including:

- The size of the minority shareholder’s interest, with smaller ownership stakes generally deserving a greater discount.

- Whether a majority shareholder exists. If there is a majority owner, the minority discount is generally greater. If there is no majority owner, a smaller discount is generally applied.

- Whether there are provisions in the Articles of Incorporation or Shareholder’s Agreement that provide protections or liquidity to the minority shareholder.

- The nature of the business itself, which may dictate the importance of operational control. For example, control over passive investment holding companies is less important than for active businesses where key decisions frequently need to be made.

- The profitability and dividend history of the corporation. Profitable companies with a stable dividend history lowers the risk that a minority shareholder will not realize a return on their investment, thus reducing the need for a minority discount.

The relationships between shareholders can also affect the extent of a minority discount. For example, if the company is controlled by a group of minority shareholders who ‘act in concert’ in voting matters, it can be argued that no minority discount should be applied all. This is the principle of ‘group control’. This is often the case where a corporation is controlled by a group of family members who collectively act in the best interests of the entire family.

Case Examples of Group Control

Group control appears to be a factor considered by the judge in Parton v. Parton (2016 BCSC 1528). In this case, the court was faced with a decision as to whether a minority discount should be applied to Mr. Parton’s 50% interest in William Parton Agencies Ltd. (“WPA”). WPA was an insurance brokerage business which had been started by his father, William Parton, but was now owned equally by Gerry Parton (the respondent) and his brother Doug Parton.

The parties had jointly retained an expert from Smythe LLP (the “Expert”), who noted that WPA was not profitable, but held a valuable asset being an ICBC Autoplan license. The Expert valued the company using a Liquidation Approach and opined that Gerry Parton’s 50% interest in WPA shares had a fair market value of $602,000 with no minority discount applied and a fair market value of $391,000 with a 35 per cent minority discount applied. The valuation of the WPA shares with no minority discount assumed that Doug Parton would agree to sell his interest in WPA together with Gerry Parton’s shares. The valuation with a minority discount assumed that Doug Parton would not act in concert with his brother and would not sell his WPA interest.

The judge considered Mr. Parton’s assertion that a 35 per cent minority discount should apply based on Doug Parton’s evidence that he did not want to sell his WPA shares and intended to give them to his nephew, Spencer Parton, who became involved in the family business a few years earlier. However, the judge rejected this position. Based on the whole of the evidence, he went on to find Doug Parton would make decisions based on his own best interests, which would be to sell his WPA shares together with his brother, noting that WPA is an unprofitable business “by quite a large magnitude”. Taking into account the foregoing, the judge concluded that a minority discount did not apply, and the current value of Mr. Parton’s WPA shares was $602,000,

Mr. Parton appealed the decision, challenging the judge’s finding that a minority discount did not apply to the valuation of his non-controlling interest in a family business, and he sought an order reducing the value ascribed to the shares. In Parton v. Parton, 2018 BCCA 273, the BC Court of Appeal upheld the trial judge’s decision that no minority discount was applicable in valuing Gerry Parton’s 50% interest.

The judge appears to conclude that the most likely transaction scenario would be a joint sale of both brothers’ 50% shareholdings to a third party. In most cases, the court is trying to determine a fair market value for a specific interest (that is the family property) and does not consider the motivations or intentions of other shareholders. This may be a good example of the principle of ‘group control’ described above.

Another example where the court applied the principle of group control and rejected the application of a minority discount is JAC v VRC2. In this example, the minority shareholder was part of a group of shareholders who had historically acted in concert to their mutual benefit, and would likely continue to do so, including eventually selling their collective interests together.

Support for the application of a minority discount is found in Balcerzak v. Balcerzak (1988), 41 R.F.L. (4th) 13 (Ont. Gen. Div.) However, (at para. 29) the judge does recognize the principle of group control:

… I do not consider that the discount should be very high where all of the other shareholders hold similar minority interests, particularly where the shareholders are a close family unit that have worked together for many years and will probably continue to do so for many years to come. …

Conclusion

The application and quantum of a minority discount is highly subjective and dependent on numerous case-specific factors. Please contact one of our valuators if you require assistance in this regard.

1 See “An Analysis of Trends in the Application and Quantum of Minority Discounts in Canadian Court Judgments, 1986-2015” (Prem M. Lobo and Stephanie Dexter).

2 See JAC v VRC, 2015 YKSC 15 at Par. 167 and 168