Challenges to Owning Canadian Real Estate as a Foreign Resident

With tax season officially upon us, now is a good time to look at recent federal laws that the government says are about “curbing speculation and ensuring that houses are used as homes for Canadians to live in—and not used as financial assets for foreign investors.”

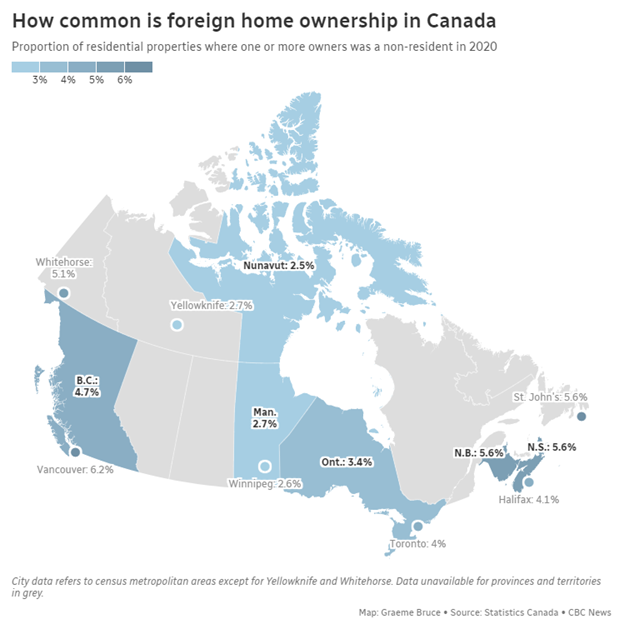

For background context: some statistics suggest that non-Canadians only account for 6% of homeowners in Ontario and British Columbia and nationwide house prices average around $750,000+ against a median net household income 11 times lower. Per the BBC, housing prices in Canada rose 48% between 2013 and 2022, while the median after-tax household income grew 9.8% between 2015 and 2020.

The first major development on this front is the Underused Housing Tax (UHT) that received Royal Assent on June 9, 2022. If you would like to read a detailed breakdown of the UHT, you can read the blog we recently published about it. Here is a quick recap:

The UHT is the first federal statute designed to discourage foreign ownership of vacant Canadian real estate properties. Effective January 1, 2022, the 1% tax is imposed on every person who is an owner (other than an excluded owner) of a residential property in Canada on December 31 of a given calendar year. Most non-citizens and non-permanent residents of Canada that own a residential property in the country will not meet the definition of an excluded owner and, therefore, will be subject to the UHT.

At the time, the government said the UHT would “help free up homes for Canadians to live in, make the housing market more affordable for Canadians, and ensure that foreign, non-resident owners of Canadian housing pay their fair share of Canadian tax.”

In the 2022 fall budget statement, alongside the UHT, the federal government had also proposed a two-year ban on some foreigners buying homes in Canada. After it received Royal Assent, the Prohibition on the Purchase of Residential Property by Non-Canadians Act came into effect on January 1, 2023. The law “prohibits people who are not Canadian citizens or permanent residents from buying residential properties” for the next two years, with an associated penalty of $10,000 for violating it. Contracts that were signed before the enactment date will be grandfathered.

Per the regulations, the ban’s applicability is limited to the “Census Agglomeration and Census Metropolitan Areas” as defined by Statistics Canada and determined by the most recent census data. As per Statistics Canada, a Census Agglomeration (CA) “must have a core population of at least 10,000”, while a Census Metropolitan Area (CMA) “must have a total population of at least 100,000, […] of which 50,000 or more must live in the core”.

In British Columbia, for instance, cities like Vancouver, Abbotsford, Victoria and Kelowna would qualify as CMAs, while smaller areas like Squamish, Vernon and Parksville would be CAs.

The ban covers various types of properties, including land that is zoned for residential or mixed use, or has a residential dwelling on the property (including detached houses, semi-detached houses, row homes, condominium units, etc.) and the share of common property, containing not more than three dwelling units.

In addition to individuals, purchases made by corporations and entities where there is control by a non-Canadian are also prohibited by the new law.1

So, what happens if you’re a non-resident and want to buy property in Canada? To do so, you’ll now have to meet one of the exemptions, which include (but are not limited to): international students who have resided in Canada for at least five years; individuals claiming refugee status in Canada; and individuals with a valid temporary work permit who have worked full-time in Canada for the three years prior to purchasing the property.

This law is just the latest in a series that is intended to deter non-Canadians from buying property in Canada that will not be their primary residence (i.e., “investment” properties that will be left vacant or underused). Some of these laws have significant penalties attached if you fail to meet reporting obligations and payment deadlines.

If you are worried that you might fall into one of these categories and need help determining what to do, reach out to one of our qualified tax experts today.

1Here defined as the “direct or indirect ownership of shares or ownership interests of the corporation or entity representing 3% or more of the value of the equity in it, or carrying 3% or more of its voting rights; or control in fact of the corporation or entity, whether directly or indirectly, through ownership, agreement or otherwise.”