Making the Case for Eliminating the New Housing GST Rebate

By Gary Luedke

When the Goods and Services Tax (GST) was introduced in Canada in 1991 (initially at a rate of 7%) it was intended to mimic Value-Added Tax (VAT) systems in other “developed” countries. The roll-out, however, was characterized by numerous complications, largely resulting from the many policies, exemptions and transitional provisions laid out within. In addition, little has changed with the GST rules in the ensuing three decades.

Policies include exemptions and zero-rated sales such as medical, food, exports and used residential housing. Especially pertinent to this discussion is the fact that when the GST was being enacted, the government simultaneously eliminated a hidden Manufacturers Sales Tax (MST). As regards the real estate and construction industries, in 1991 both newly built and substantially renovated housing were then subject to GST.

When making these new frameworks, the government was meticulous, and developed well-thought-out considerations. Authorities took great care to fully analyze the impact the program’s implementation would have on the economy. One example of this was the consideration of paying MST hidden in the 1990 costs of new homes under construction at the time of the introduction of GST. Subsequently, GST would be added to those new homes that were under construction on January 1, 1991. The government built-in transitional provisions for builders to ensure they could recover the estimated MST on homes under construction in December 1990.

It would seem simple that new housing would be subject to what is now 5% GST on the purchase, much like in the case of property transfer tax and other closing costs.

Another example of the care taken at the introduction of GST was the new home rebate program. The New Home GST Rebate Program was aimed at those buyers who intend to use the property as their principal residence. This is a holdover from the initial roll-out, though, over time, a residential rental property rebate was also introduced for those who purchase a home as an investment that they intend to lease out. This latter rebate has a one-year hold requirement and is even available to foreign investors/buyers.

The GST rebate rate determined in 1991 is still the rate today – 36% of GST on new homes is eligible for a rebate, subject to certain limitations. The government recognized that 7% GST was significantly more tax than the previous MST content in new home. They landed on that rebate percentage as it was calculated that the net GST on a new home (after the rebate was applied) is similar enough to the estimated 4% MST included in the construction cost of new homes before 1991.

However, that 36% rebate figure was based on a GST rate of 7%. It has not been adjusted to account for today’s lower rate of 5%. An additional complication was that, when it was implemented, the 36% rate was based on fair market value purchases of $350,000 or less, with the rebate phased out on values over that before being eliminated by $450,000.

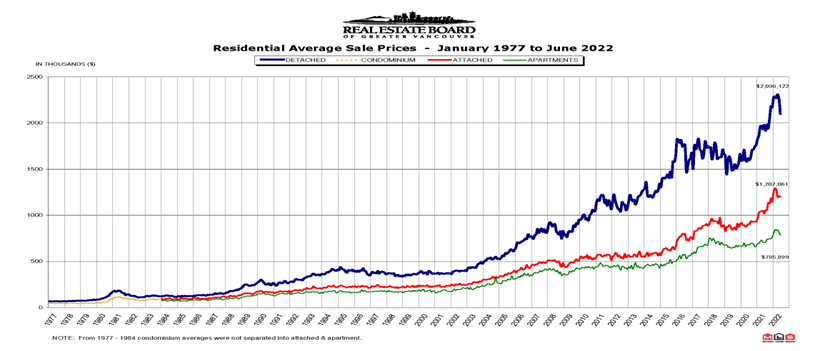

This was mainly because, in 1991 the Canadian government’s policies tended to be progressive, with wealthier citizens having to pay extra taxes. This is still the case today. But while the average price of a home in Canada was $120,000 three decades ago, today the national average is over $800,000, with homes being even more expensive in British Columbia. Thirty years ago, virtually every new home nationwide was eligible for this rebate, except, perhaps the most expensive ones (think those in the west side of Vancouver, West Vancouver and better areas of Toronto).

In other words, the average home in Canada costs nearly 7 times more today than it did in 1991, but the total rebate amount has remained static, capped at $6,300. Very few new homes – if any – in the Lower Mainland would meet that eligibility threshold today.

The graph below shows the average sale prices for residences in the Greater Vancouver area from 1977 to today.

Given this dramatic increase in the price of new homes, there is little doubt that first-time home buyers still need programs to assist them in their purchases. However, it is becoming increasingly obvious that the new home GST rebate program – in its current avatar – is losing relevance. There is no dearth of assistive programs in 2022, including (but not limited to):

- The RRSP Home Buyers Plan, introduced in the 1980s, which allows a $35,000 withdrawal from an individual’s RRSP (up to $70,000 for a couple) to purchase a first home, without income tax being levied. In 2019, it was even increased from $25,000.

- The CMHC First-Time Home Buyers Incentive, introduced a few years ago, which used 5% or 10% shared equity mortgage (5% to 10% for new).

- The Tax-Free First Home Savings Account announced just a few months ago in the 2022 federal budget, which works in a similar way to the RRSP Home Buyers Plan, with some tweaks.

- A $750 First Time Home Buyers Credit that was introduced in 2009 and that will increase to $1,500 this year.

- BC specifically even has a Land Transfer Tax rebate program for first-time home buyers.

Now, compare these to the New Home GST Rebate Program, which has not changed one iota since its introduction in 1991. The 36% rate, picked as an equivalent figure to the old MST, is obsolete. Not to mention, one particularly galling loophole is that foreign buyers are still eligible for this GST rebate, even though provincial governments have enacted penalties against foreign buyers, like the 20% additional property transfer tax in BC. The federal government has also proposed not allowing non-recreational residential housing sales to foreign buyers for 2 years.

If the government is not going to update the program – and certainly, there has been notable reluctance on their part to adjust old GST programs as a whole – then maybe it would be best to put it out of its misery. There are numerous alternatives that first-time home buyers can consider instead, and they are no longer reliant on this $6,300 rebate on a purchase that can cost $800,000 or more.

While they’re at it, might I suggest they also update the $30,000 annual revenue small supplier threshold above which a small business is required to register for GST? It is laughable to compare $30,000 in annual business revenue in 1991 to that same $30,000 in 2022.